Teachings of Convenience

Editor's note: This article was marked "open to all" when originally published, so we understand the material to be in the public domain.

Aparimana

Cambridge, Jan 2017

Open to all

I am extremely glad that Sangharakshita has made his recent statement, acknowledging (among other things) that “Triratna sometimes bears the mark not of the Dharma but of my own particular personality”.

I hope this may be a turning point that will finally allow the Order to work through, resolve and leave behind the controversies that have dogged us for so long. I believe that some kind of effective “Truth and Reconciliation” process is essential if the Order is going to survive in the long term.

Below is something I wrote a month or so before the statement, which discusses issues around the relative influences of Sangharakshita’s personality vs the Dharma, and suggests what may be necessary for successful “Truth and reconciliation”.

The key point, I believe, is to understand that the “sex and kalyana mitrata” episodes are not isolated aberrations, but just the most prominent and visible manifestations of deeper factors in Sangharakshita, which in turn have influenced the culture of the Order. I believe that a deeper appreciation of these kinds of factors will be essential to “Truth and Reconciliation”.

I see three main factors which came together to create the “sex and KM” episodes.

The first, most obvious one is that Sangharakshita was overpoweringly attracted to young men, as he himself acknowledges. In its own right, this might not be particularly troubling, beyond the fact that compulsive craving indicates rather limited progress on the Buddhist path.

I think there may be some who would like to see this as the only issue, and to regard it as roped off from the rest of who he is. Then they can still maintain that Sangharakshita is a great Buddhist teacher, but with an isolated weakness that has not affected the rest of his work or teaching.

But of course, there was much more going on to make these episodes so damaging, and these other factors cannot be compartmentalised - they are part of who Sangharakshita is, they have leaked out into the rest of his life, and have become incorporated into the culture of the movement he founded.

The second of the three crucial factors is around Sangharakshita’s truthfulness.

Given the central role that truthfulness plays in the Buddhist path, many people will assume that Sangharakshita is very honest, and it may be important to them to be able to see him in this light. Subhuti, for example, wrote in Shabda (August 2010) that: “I have never found him to have lied in the forty years I have known him”.

However, although Sangharakshita might not tell explicit “black is white” lies, in my experience he uses half truths and misleading facts.

A team of psychologists have recently introduced the term “paltering” to the study of deception: “Rather than misstating facts (lying by commission) or failing to provide information (lying by omission), paltering involves actively making truthful statements to create a mistaken impression.” I think this is a useful term when considering Sangharakshita’s truthfulness.

I have many examples in mind - I have included some of them in an appendix at the end of this piece - but for present purposes, a well known example illustrates the point. Sangharakshita used to encourage heterosexuals to experiment with homosexuality, and used the expression that it was as trivial as changing from tea to coffee. The very strong implication is that this was his own experience, yet we know that he was drawn irresistibly to young men exclusively. Sangharakshita has since pointed out that he never explicitly said “I am heterosexual” - that may well be true, but nevertheless, I believe it is no accident that he succeeded in communicating this idea widely in the Order. For example one Order Member posted on a public forum that “Sangharakshita has said [and I do not quote] that his natural preference is heterosexual, but that changing over is about as difficult as changing from tea to coffee”.

This tendency to mislead, albeit without explicitly lying, is not limited to his sexual relationships - it is a theme throughout his communication, it cannot be compartmentalised as just a blind spot around sex. It has been an important factor in how he has related to the movement, and inevitably, it has also influenced what some order members consider to be acceptable communication.

And this brings me to what I think is the third factor in the ‘KM sex’ issue. In my observation, Sangharakshita does not strive to faithfully communicate the Buddha’s teaching; rather, he cherry picks what he wants from the Buddhist tradition in order to put across his own message.

An Order Member who spent a good deal of time with Sangharakshita put it like this:

For Bhante 'Tradition' is not some sort of recommendation. When he uses the word 'tradition' that is just Bhante addressing the Buddhist world out there to which he is forever bonded by making out that he is a Buddhist in the first place. He does not care about tradition he just finds it tickles his fancy when he encounters similarities between his approach and the historical tradition. So he always mentions it when he sees it not because he is impressed by tradition but in a sort of sociology of religion kind of way. [...] He appeals to tradition when it suits him to do so.

Since Sangharakshita has not felt obliged to faithfully communicate what the Buddha taught, there has been plenty of room for Sangharakshita’s teaching to be influenced by his tastes and desires, to the point where it often takes leave of the Buddhist tradition altogether and cannot make any claim to be an expression of the Dharma.

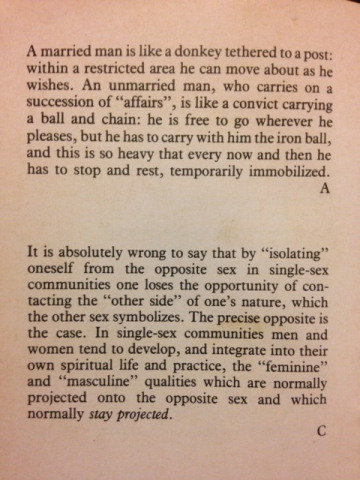

Where the needs of the teacher influence the teaching, you find “Teachings of Convenience” - teachings that are given primarily because the teacher finds it convenient for their disciple to believe them, rather than because the teaching is helpful to the recipient. Our movement’s culture abounds in Teachings of Convenience. The teachings on “Greek Love” were, of course, archetypal Teachings of Convenience, and few would now try to claim the they were authentically expressing the Dharma taught by the Buddha. However, Teachings of Convenience are not limited to a blind spot in the area of sex, they are ubiquitous in our culture. This is not an isolated flaw in an otherwise great Buddhist teacher. I list some more examples of “Teachings of Convenience” found in our culture in an appendix to this piece.

While Teachings of Convenience have been used to get people to do whatever is required at the time, in the background, Sangharakshita’s tastes have shaped the overall trajectory of his teaching to the point where now, since the seven papers, we are working within a framework that only appears to be “Buddhist” beyond the first few steps because of the use of Buddhist words. We now have an entire doctrinal system based around the psychology of inspiration, imagination, and ascent to angelic states of being. However beautiful this may be (and it is not without value), it is leading people along a path fundamentally different from the one Buddha taught, where freedom is primarily found by a penetrating awareness of ordinary immediate experience. Sangharakshita’s recently codified teaching describes a path to heaven, not a path of liberation.

This non-Buddhist doctrinal framework has only become crystal clear in the last few years with the codification of Sangharakshita’s teaching in the seven papers, however, the underlying psychology has been at work for a long time, and it has been essential in allowing abuses to take place. This ‘stairway to heaven’ model supports ideas like giving yourself up to the higher will of your teacher; relying on inspiration to carry you through immediate difficulties and reservations; and disregarding your own needs in order to contribute to some higher good. It is much easier to manipulate people who are inspired to give themselves up to something higher than it is to manipulate people deeply grounded in their immediate experience.

Again, this is not a small oversight of an otherwise great Buddhist teacher, but an indication that Sangharakshita is not always a faithful exemplar, or teacher, of the Buddhist path.

Sangharakshita is impressive, of course; many people are attracted to this, and assume that talent and charisma are necessarily marks of progress on the Buddhist path. However, they they are not. I can agree that Sangharakshita is ‘immense’; that he is highly intelligent with a huge knowledge of art and culture; that he is charismatic and has a powerful effect on people who are receptive to him; that he can be kind when it suits him to be kind; even that he has a touch of magic to him. However, none of this is proof of being an accomplished practitioner of the Buddhist path.

Over the years, Sangharakshita has undoubtedly spoken at times with insight and clarity about the Dharma and Buddhist tradition - he has much of interest and importance to communicate, and much of his earlier teaching is authentically Buddhist. However, it is not possible to rely on his teaching uncritically. A true Buddhist teacher needs to be better than just “good in parts”.

I don’t think that Truth and Reconciliation is going to be possible without letting go of the idea that Sangharakshita is a great Buddhist teacher, because it makes it impossible to see the situation for what it is. If you carry the assumption that Sangharakshita was honest and has faithfully taught the Dharma, then you miss the fact that it was precisely the dynamic of deceit and manipulation through bogus “sex and Kalyana Mitrata” teachings that has made the sexual episodes so painful for those affected. Those who have been hurt feel that they have been duped and used because they have been duped and used, not due to some innocent misunderstanding. As long as Sangharakshita is seen as a great Buddhist teacher, it is very hard to avoid “victim blaming” - after all, if something has gone wrong, surely it cannot be because the Great Buddhist Teacher has acted immorally?

Sangharakshita’s ways of being have, inevitably, become incorporated into the culture of the movement he founded. To see Sangharakshita’s shadow side is to see the shadow side of our movement’s culture. Genuine Truth and Reconciliation will heal not just the immediate victims, but the culture of the movement too.

I realise that this is not going to be easy, though. I have noticed over the years that for some order members, Sangharakshita is a symbol so deep in their psyche that it is absolutely untouchable. From what I can make out, for these people, reverencing Sangharakshita is not just spiritually but psychologically essential. This makes realistic discussion of Sangharakshita’s dark side quite impossible, since it would feel like an existential attack - and for good reason, since losing this glowing symbol would shake up their psyche so much that the consequences could be damaging. Unfortunately, I just don’t see how Truth and Reconciliation is going to be possible for anyone in this situation.

There will be many others whose psyches are not totally dependent on maintaining a sacred projection onto Sangharakshita, but who do see the order so much in terms of him, that to discredit him would be to discredit the Order. These people may see Sangharakshita as the source and guarantor of all our teaching, and see order members as essentially passive recipients of his system. For those who see the order in this way, what I have written above may seem like an attack on the Order, even an attempt to destroy it. For such people, I suspect that Truth and Reconciliation is only possible hand-in-hand with a re-visioning of the Order. We can come to terms with the past and move on if we see Sangharakshita not at the great teacher who provided a complete system, but as the founder of our community who introduced us to the Dharma.

If we see Sangharakshita as having given us a starting point, rather than a finished product, then his flaws do not matter much, because we are responsible for sorting out the wheat from the chaff, and evolving the Order in the light of our own insight and practice.

APPENDIX 1 - Paltering and misleading: more examples

I include more examples somewhat flinchingly - I do not want to organise a character assassination, however, the idea that Sangharakshita is often not honest has to be backed up…. So here are a selection of relatively clear-cut cases:

During the ‘Triratna’ name change process, an order consultation was started. However, it was quickly abandoned when Sangharakshita told Mahamati that he had not requested a consultation, and that the name change was to go ahead on his own authority. When an order member asked Sangharakshita, during a visit to Cambridge, why Sangharakshita had felt it necessary to impose his will on the order regarding the name change, Sangharakshita responded that it would be “grotesque” for him to impose his will on the order. True enough; however, the very strong implication is that he therefore did not do so, but of course, he did impose his will on the order in this matter. A perfect example of “paltering”.

Sangharakshita claimed (or allowed others to claim on his behalf) that he had been celibate since the 80s, including wearing the golden kesa in public. Most people would understand this to mean having abstained from all sexual activity. However, it turns out that he had been having sexual contact with a young man during this period. It seems that he justified this by invoking a very narrow definition of ‘celibacy’ …. By his own definition of ‘celibacy‘ (ie not having ejaculated), he was telling the truth, but he was also undoubtedly misleading others, and few would consider this to have been honest.

Sangharakshita allowing the order in India to believe that he was a celibate monk for many years. Again, he might never have explicitly said “I am a celibate monk”, but how else would wearing the robes of a bhikkhu in India be understood by the Indians?

In the recent papers, Sangharakshita addressed his teaching that “you can change anything but the Going For Refuge”. He said that he merely mentioned the idea casually once or twice, and that for some reason people picked up on it. However, according to those I have spoken with who were around at the time, this teaching was something Sangharakshita pushed very frequently and forcefully for a period of time. Why does he now say that it was something he only mentioned casually once or twice? Has he really forgotten, or does he want to rewrite the past?

On the same issue, Sangharakshita also states that this teaching has been misinterpreted, and should never have been taken literally. This is surprising, to say the least - the literal meaning is perfectly coherent, particularly in a Buddhist context where teachings are understood to be means to ends, and as far as I know, he has never before discussed any hidden meaning. Yet he now says that this should be understood not literally, but as an example of an Indian literary device, meaning almost the exact opposite of its apparent meaning, ie something along the lines of “you cannot change anything, and most of all, you cannot change the GFR”. I do not believe this to be an honest or straightforward account. I believe that an honest response would be “I no longer support what I said then; I have changed my mind”.

A simple factual case: what does “Sangharakshita” actually mean? According to linguists I have asked, it undoubtedly means “protected by the sangha”, just as Buddharakshita means “protected by the Buddha” (after all, how could a bhikkhu possibly protect the Buddha?). Why should Sangharakshita have interpreted it to mean “protector of the sangha”? If it was an honest mistake, it is surprising that it endured for so long. Although perhaps of little importance on its own, it seems to indicate a temptation to “self mythologising” which is not entirely honest.

Similarly, why did he continue to use the term “Maha Sthavira” (which is intended to apply to bhikkhus who have kept the vinaya for decades), long after he ceased to be a bhikkhu? Was that an honest mistake?

APPENDIX 2 - Teachings of Convenience: more examples

What distinguishes a “teaching of convenience” is not that it is given to address a particular current situation (for example, teaching about harmony if there have been arguments is not a “teaching of convenience”) but that it is primarily given not to fulfill a need for the student, but because it would be convenient for the teacher if the teaching were believed and followed. The teaching may or may not be legitimate in its own right - the key is, for whose benefit was it given?

Most of these examples are taken from Order culture rather than being attributable directly to Sangharakshita - however, surely the culture has evolved like this thanks to his example.

One of the first times that I became aware of this tendency was during the seminar that Sangharakshita gave to Windhorse Trading around 1994. Windhorse management had prepared a list of questions, many of which seemed, to my ears, to be requests to override existing teachings which were inconvenient to the agenda of Windhorse management. Every single item on the list was ‘approved’ in what seemed to be a rubber stamping exercise, Sangharakshita giving his authority to whatever line Windhorse management wanted to propagate.

So, for example, some Windhorse employees had been complaining that constant frenzied hard work, praised as “developing virya”, was all very well, but were the five spiritual faculties not meant to be kept in balance? Where was the spiritual benefit in living a lifestyle so hostile to meditation?

Sangharakshita approved a new teaching - the spiritual faculties do not need to be kept in balance in the short term. This could then be interpreted to mean that it was OK to lead an entire lifestyle that emphasised virya at the expense of samadhi for months or years on end. Whatever the merits of this view, I found it shocking that it was ‘approved’ so glibly. It seemed that teachings were being created on demand to prop up a profitable situation and silence legitimate Dharma-based criticisms.

Some “teachings of convenience” are relatively innocent, but illustrate the point well. For example giving a talk on the spiritual benefits of dana just before asking for donations - is this “teaching” really given primarily for the benefit of the students or the teacher?

An example from my time during the Ordination process …. Some mitras had been finding it difficult for their going for refuge to be recognised by their local chapters, and were finding that trying to ‘prove’ that they were going for refuge effectively was getting in the way of actually practicing. Their view was “I know I am effectively going for refuge, I will just wait patiently until it is recognised”. Subhuti’s response was a new “teaching” - it is impossible to go for refuge effectively until it has been recognised, ie until one had actually been ordained. I cannot know his motive with certainty, but it struck me at the time that this “teaching” was quite bizarre in its own right, but seemed to have the effect of re-establishing the centrality of the ordination process, which might be undermined by the idea that a mitra could be happily going for refuge effectively, and getting on with his practice, without it being recognised.

A theme in some of the “teachings of convenience” I have noticed is to simply deny that there is any tension between two things. For example, in any religious organisation it must be a common observation that the ecclesiastic hierarchy is not identical with the spiritual hierarchy - that some people may specialise in organisational responsibility, and even rise high up this hierarchy, without having necessarily made great spiritual progress; while others might make great spiritual progress but shun organisational responsibility. Of course, to acknowledge this is very inconvenient for the ecclesiastic hierarchy - their job is much easier if people assume that they speak with both organisational and spiritual authority. During my first Convention on returning from Guhyaloka, Subhuti delivered his talk on the path of responsibility, which essentially teaches that within the Order, these two hierarchies are one. If this teaching is believed, in spite of the well-known tension between ecclesiastic and spiritual hierarchies, it will both increase the power and authority of those with official responsibility, and also make it easier to recruit people into positions of responsibility. I do not think that these convenient side effects are accidental.

Surely it would have been more truthful and helpful to explore the tensions between these two hierarchies? Sometimes a “teaching of convenience” involves suppressing an “inconvenient truth”; so, for example, Sthiramati wrote a piece for Golden Drum entitled “Buddhism and Hierarchy: a historical perspective” which showed how the tensions between different hierarchies had been managed over the 25 centuries since the time of the Buddha. However, it was pulled from publication at the last minute, not because it was believed to be untrue or unhelpful, but because it inconveniently appeared to contradict what Subhuti had written in his Golden Drum article “Ascending the Spiritual Hierarchy”.

Add new comment